Articles about digital nomads often imply a false choice about life: you can either stay rooted in one place while working a soul-crushing job, or you can live on a beach in Bali and wipe sand off of your keyboard for just long enough to scrape together a living online. There’s a huge amount of room between those extremes, and I’ve been living somewhere in it.

My girlfriend Ali and I have been nomadic since mid-2018. Along the way, we have both worked full-time as digital product designers for companies based in Pittsburgh, San Francisco, and Buenos Aires. We don’t work from sparkling beaches or some newfangled communal housing enclave — instead, we work remotely from fairly modest apartments as we slowly but surely move around the world.

Beyond the many fantasy-laden articles about nomads in big publications, advice for nomads is often written by self-employed travelers who eke out a living by blogging or making videos about their own nomadic journeys. It’s a very meta subculture. Although I’ve been inspired by long-time nomads like Traveling Jackie or Nomadic Matt, I wanted to share a perspective of nomads with no connection to travel or digital nomad communities online.

Nomadic life can come in many forms. As context for the article ahead, here is a quick explanation of our nomadic journey so far:

- 2018 in North America: We left Pittsburgh in August, getting the hang of the nomad lifestyle close to home. We both worked for a company with an Industrious co-working membership, so we often worked from their offices. We had one-month stays in Montreal and New York.

- 2019 in Europe: We lived and worked in Europe (and a bit of Morocco). Ali left her job in August while I kept working. We had one-month stays in Madrid, Paris, Copenhagen, London, Dublin, Amsterdam, and Berlin, with a smattering of shorter stops throughout the year.

- 2020 in Portugal: Ali got a new job which allowed me to take a year off after 12 years of work. The pandemic struck as we arrived in Lisbon, so we stayed in Portugal for the rest of the year, moving only when safe. We stayed for a month or longer in Lisbon, Porto, Coimbra, and Tavira.

- 2021 in Portugal (so far): I started a new job in January, so we’re both working again. We spent the first three months of 2021 on a government-mandated lockdown, and the pandemic continues to make life uncertain.

Two caveats before we begin:

- Privilege: I am incredibly privileged to be able to live and work this way. Although I have worked hard in my career, I’m a middle-class white American male from a stable family, which is like being born on third base. No matter how hard I’ve worked to sprint across a metaphorical home plate, I still have huge unearned advantages compared to many people. I hope you find some value in this article no matter what your situation or background might be.

- Links: Most links to products on Amazon are referral links, meaning that I’ll make a tiny amount of money if you happen to buy something after clicking a link. Feel free to use the links for reference only — you can find anything at a local store or elsewhere online — or buy things using the links often if the article was useful to you.

This article is the length of a very short book. The first six parts are a detailed inventory of tips and lessons learned over nearly three years of life on the road. The last two parts are more introspective, reflecting on nomadic life so far and hypothesizing about its future.

Tactical advice

1. Logistics of leaving

2. Where to go and what to see

3. Lodging

4. Work

5. Travel and transit

6. Useful products and services

Big-picture thoughts

7. Reflections on being a nomad

8. Nomadic futures

Logistics of leaving

We started loosely planning a year in advance

Planning was casual at first because the idea of being a nomad felt hypothetical. As we became more serious about it, we made preparations:

- We synced our leases: Ali and I lived separately before this journey, so becoming nomads also meant moving in together. Six months before we left, she extended her rental so that our leases ended on the same day.

- We made a “before & after” budget: We created a detailed list of our current expenses, then another outlining our expected expenses once nomadic. This side-by-side comparison helped us see which of our expenses would go up, and which would go down. Budgeting also revealed things we didn’t know enough about yet: options for international phone service, cost differences from country to country, etc.

- We planned a rough itinerary: We talked about places we aspired to go, favorite places we wanted to revisit, places with friends or family, and any existing commitments (a wedding, in our case).

We formally proposed the idea to our company

Most leaders in companies have never had nomadic employees, so they don’t know if it will work. With a printed proposal in-hand, we pitched the idea to our CEO and COO with a detailed list of positives, negatives, and potential opportunities that we anticipated if they accepted our proposal. We included a draft of our itinerary for the upcoming year and notes about how we planned to stay productive on the road.

Thankfully, our leaders were receptive to the idea, if only because several other full-time employees were already working remotely. We proactively made a few promises to make our proposal more palatable:

- Addresses: We would have US-based addresses for mail, taxes, etc.

- Time zones: As we moved around the globe, we would always work US Eastern time so that our coworkers could rely on our schedule.

- Cost: We would pay for extra technology gear or services so that our company didn’t incur new expenses because of our lifestyle choice.

- Gradual start: We would start our journey in North America to get our feet wet before venturing to Europe.

Because of the proliferation of remote work in 2020 due to the pandemic, I assume future nomads will have an easy time making the case compared to us in 2018. The stigma and skepticism around remote work is quickly vanishing.

We moved out of our apartments

Moving to nowhere-in-particular required a few big logistical steps:

- We changed our permanent addresses. I officially live in Arizona with my parents, and Ali lives in Minnesota with her mom. We have local driver’s licenses, pay local taxes, vote in local elections—the works. In rare instances where we get mail, our families are kind enough to send us photos. Having employees in two extra states slightly complicated our company’s tax burden, but there was plenty of precedent with previous employees, so they were okay with it.

- We sold or donated our largest belongings. Renting a storage unit is expensive as hell. For example, storing a big couch for 12 months might cost upwards of $100/month — probably more than the couch cost in the first place. We purged everything we owned, starting with the things that were physically largest. I took photos of my stuff, built a quick website using Squarespace, and put up flyers in my apartment building. That was surprisingly effective — almost everything sold within a few days, and coordinating with people in my building was easy. I used Facebook Marketplace to unload what was left.

- We put the rest of our stuff in storage. My remaining belongings are collecting dust in a Pittsburgh storage unit. When I found a storage space I wanted to rent, I taped a rectangle on my apartment’s floor to match its exact dimensions, which I filled up as I packed. By the time we moved all of it into storage, I knew exactly what would fit in the small space. Ali’s stuff is in her sister’s unfinished basement in Minnesota. If a friend or a family member has plenty of room, this is a great option because even a small storage unit’s cost adds up quickly over time.

Where to go and what to see

Multiple factors influence our route

- Time zones: Our co-workers are primarily based in the US, and we need to have some overlap with them in our working hours. That restricts our travel to North America, South America, Europe, and Africa. We both love traveling in Europe, so we’ve spent most of our time there.

- Weather: We move with the weather to avoid extreme hot and cold. We try to stay in Southern Europe during the winter and Northern Europe during the summer to avoid climatic extremes.

- Visits from friends and family: We weren’t surprised that people offered to let us stay in their houses, but we were surprised how many friends and family came to visit us on the road. We have periodically bent our itinerary to match other people’s availability and travel schedules.

- Cost: We avoid the most expensive parts of Europe (e.g., Switzerland and Scandinavia) in favor of more affordable locales.

The Schengen Zone dictates most of our European itinerary

The Schengen Zone poses major logistical challenges for people wanting to live in Europe as a nomad. The Schengen Agreement allows Europeans from 26 countries to travel passport- and visa-free within the zone, but the zone affects visitors from outside the Schengen area too. Americans are allowed to be inside the zone for a total of 90 days within any 180-day window. That sounds reasonable, but it’s surprisingly restrictive. For example, if you visit Iceland for two snowy months starting in January, then bask in the sun on the beaches of a Greek island for five weeks in June and July — surprise, you’re an illegal immigrant! You just spent more than 90 days in the Schengen Zone during a 180-day window.

A few places in Europe are outside of the Schengen Zone, although the zone expands periodically, so it is worth researching the latest situation. The UK and Ireland are completely out of the zone, as is most of the former Yugoslavia (Bosnia, Croatia, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia). The easternmost parts of Eastern Europe are also outside of the zone (Belarus, Bulgaria, Moldova, Romania, Russia, and Ukraine). Several Europe-adjacent countries are handy for replenishing time in the Schengen zone without traveling too far away (Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Israel, Turkey, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Armenia). Every other country in Europe is in the zone, so it’s essential to carefully count days to ensure you’re not an accidental illegal immigrant. Useful resources related to Schengen:

- Nomadic Matt wrote a helpful article with advice and legal loopholes for people wanting to spend more than 90 days at a time in central Europe. The discussion at the bottom is useful too.

- The Lonely Planet Thorn Tree forum’s Schengen post has a wealth of information on the subject, although you’ll have to read through pages and pages of questions and answers. Fair warning: the Lonely Planet Thorn Tree is littered with smug assholes and has been unwaveringly unwelcoming since its origin many decades ago. Still, it’s an invaluable resource, especially if you read thoroughly before daring to ask a question. (I once visited the physical thorn tree in Nairobi that is the forum’s namesake, and it was plastered with sweet and endearing notes from one traveler to another. The internet brings out the worst in us, I guess.)

- Adam Bard built a Schengen calculator that allows you to input stretches of time you plan to spend in Schengen to ensure your itinerary doesn’t violate the law. There are other calculators, but this is my favorite.

- As of early 2021, there are so-called digital nomad visas in countries like Estonia and Croatia, which sounds fantastic in theory, but I question their usefulness. From what I can tell, they’re a ploy by tourism boards to get young tech-oriented people to live in those countries for an extended period of time — and thereby, ironically, not being as nomadic. These visas may actually increase complexity for nomads compared to just officially living in your home country and deftly navigating short-term tourist visa limitations as you go. I expect that in the next few years, we’ll see many more countries explicitly accommodating digital nomads. I set a Google Alert for “nomad visa” to get a daily recap of the latest changes.

We frequently use guidebooks as a tool

Some hardcore travelers think guidebooks get in the way of fully experiencing a place, but I subscribe to travel writer Rick Steves’ mentality that “guidebooks are $20 tools for $3,000 experiences.” They’re a must-have.

- My favorite guidebooks are Rick Steves’ charming albeit slightly dorky guidebooks about Europe. His books exclude some cities or entire regions, so they’re opinionated rather than comprehensive. His website has a generous amount of freely available content about countries and cities, so we tend to use his website for short stays in a city and buy his books for longer stays. Although fantastic overall, my only quibbles with Rick’s guidebooks is that there is a bit too much focus on churches, too little depth on modern culture, and the suggested times (“Allow about two hours”) should generally be doubled.

- Lonely Planet’s budget-conscious and information-dense guidebooks are fantastic. However, their full-sized city guides (e.g., Madrid) have way too much information for a stay of a month or less. The pocket versions covering many major cities (e.g., Pocket Madrid) are much more succinct while still providing plenty of information for a month-long visit. Their country (e.g., Spain) and region (e.g., Andalucía) guidebooks are good too. I avoid the guidebooks about entire continents (e.g., Europe) because each city and country's information is too thin, although these books are good for inspiration. The itineraries section toward the beginning of each Lonely Planet is especially helpful for getting a sense of where to go, and each includes some excellent off-the-beaten-path itineraries. It’s the first thing I look at when I’m researching an unfamiliar place.

- Guidebooks are a challenge for nomads because they’re heavy, bulky, and you only need them temporarily. Usefully, Amazon’s Kindle Unlimited service — like Netflix for books — has almost every Lonely Planet guidebook included in the subscription. Having digital versions of any destination’s book for 10 bucks a month is a good deal. Sadly, the formatting of the Kindle versions is woefully dumpy compared to the printed editions. Still, it’s good enough to be usable, and it’s certainly lighter than carrying a bunch of physical guidebooks. My preference, however, is to buy PDFs of entire books and specific chapters directly from Lonely Planet’s website, which keeps the nicely designed formatting intact. Alternatively, we just buy a physical guidebook at a local bookstore and ditch it when we leave town by donating it to an Airbnb or leaving it in a busy public space with a “free” sign.

- Due to the pandemic, assume that a city’s restaurants, hotels, and sights may have changed a lot. Guidebooks will probably be inaccurate for many years as the world recovers.

We watch travel shows & read lists to get inspired

Watching travel-oriented TV shows is an entertaining way to learn about what countries and cities pique our interest.

- Rick Steves’ Europe tends to focus on sightseeing and local history and offers useful overviews of many European cities and towns. All of the episodes seem to be available for free on his website and have no location restrictions, so they’re always watchable as we travel.

- Anthony Bourdain’s No Reservations and Parts Unknown shows offer a fantastic and opinionated look into local food, with a mild dose of history and politics. Sadly, since his death in 2018, these will get quickly out of date and become less helpful for travelers.

- Somebody Feed Phil is an endearing food-oriented travel show on Netflix and is a fun introduction to the greatest hits of a country’s food scene. The show often has inspiringly candid and casual chats with local people.

- Rudy Maxa has a show available on Amazon Prime covering many global destinations, but he’s dorky enough to make Rick Steves seem like Mick Jagger, so we only watch those when we’re bored or desperate.

- Globetrekker was a fabulous travel show that aired in the early 2000s, but its episodes are outdated enough at this point not to be very useful. (For example, a fascinating episode about once-safe Lamu, Kenya, almost led me to stupidly venture into a region now occupied by the terrorist group Al Shabaab. Travel advice can get outdated quickly.)

Travel websites and apps are good for supplemental advice

There’s a slew of travel apps out there, most of which haven’t really stuck for us. We do use a few websites and apps for research, however:

- Atlas Obscura lists quirky and offbeat sights in many cities. The places featured can be hit-and-miss and often have limited opening hours, but it’s a good supplement to a typical guidebook.

- Culture Trip has an article for many cities with pithy and interesting descriptions of different neighborhoods. Sometimes we use this to learn where to live (or avoid) in a city. Culture Trip also has decent listicles highlighting a city’s best restaurants, coffee shops, bookstores, etc.

- Cool Cousin hand-picks a dozen local people and has them showcase their favorite places in their hometown as if you have a cool cousin who lived in every city you visit. It’s useful for seeing where local 20- and 30-somethings hang out, offering alternatives to the worst tourist traps.

- Instagram is a questionable source of travel advice because the travel culture on Instagram is vapid, shallow, and unrealistic. Photogenic places have always been popular with tourists, but Instagram has magnified that phenomenon significantly. The truth is that traveling can be ugly, gross, or frustrating — that’s part of the adventure, but it’s not a side of traveling that you’ll see on travel-oriented Instagram feeds. Presumably, there are worthwhile resources somewhere, however.

- The New York Times has a comprehensive 36 Hours series covering many global cities with some great local recommendations mixed with some luxury boutique shopping frippery that doesn’t appeal to me. The Telegraph in the UK has a comparable 48 Hours series.

- TripAdvisor, Yelp, and Google Maps are each useful for finding decent restaurants nearby. We tend to use Google Maps, if only because the interface is clear, and it is used globally by both locals and tourists, unlike TripAdvisor, which is almost exclusively the domain of tourists.

- The US State Department’s travel advisory site is useful, especially when traveling to a country with recent political volatility (e.g., Turkey, Egypt, Ukraine, etc.). Each country has a profile with some dull and generic travel warnings, but those are supplemented with useful and detailed information about specific areas to avoid — certain neighborhoods in a city, problematic border crossings, roads with recent bus hijackings, terrorist activity, etc. Most parts of most countries are perfectly safe, but it’s worth knowing about tiny pockets of known volatility so that you don’t accidentally stumble into a dangerous area. (On a trip several years ago, I needed to take a passenger ferry outside of Nairobi that the State Department warned had frequent robberies. The ferry was unavoidable given my itinerary, so I timed my crossing for the calm of late-morning and stayed alert while on board. The detailed warning was actionable.)

We use Dropbox Paper as a hub for travel research

It’s essential to have one place to put everything we learn about different travel destinations. After some trial-and-error, I settled on a series of folders and documents inside Dropbox Paper. Each country has a folder, and major cities have their own documents within it. Sometimes we’ll make a document for a region — Andalusia in Spain, Provence in France, Tuscany in Italy — to collect information about smaller towns. I made a city and region template in Dropbox Paper so that adding new places is straightforward. The documents were all empty at first, but eventually, they have filled up with advice from friends, things we saw on travel shows, or things we read in guidebooks. This may seem like an excessive amount of organization, but it’s so helpful to have a place to collect random recommendations. Otherwise, a friend might say, “When you’re in Paris, you MUST go to this life-changing restaurant!” And then you write it on a scrap of paper, put it in your pocket, and off into the laundry it goes. Nomads and other long-term travelers need somewhere to collect that stuff. See our city template in Dropbox Paper.

We plot locations on Google MyMaps

Once we’ve collected recommendations in Dropbox Paper, we use Google’s MyMaps to plot everything we’ve collected geographically. We also map the walking tours that we’ve found in various guidebooks. These maps help us plan our time geographically — spending a morning before work exploring a specific neighborhood, for example. Making these maps may seem like a lot of work, but they only take a few hours to make, and they are a great way to rapidly get a feel for the layout of a city as we arrive. I often make one on our first day living in a new city.

Guided and self-guided tours help us enjoy a place more deeply

We almost always take a tour of our new home town shortly after moving in. In a bigger city, we’ll do several tours. Here are my favorite options:

- Rick Steves has excellent self-paced audio tours of many cities and museums. The audio tours and corresponding maps are available for free in the slightly buggy Rick Steves Audio Europe app, or the audio is available in any podcast app. The tours are great despite their occasional corniness. Comparable tours are available in his guidebooks, but the audio allows you to keep your head up rather than buried in a book. Only about 30% of his tours are available in audio format, however.

- Lonely Planet Pocket: Every Lonely Planet Pocket city guide includes 4–7 self-guided walking tours. They’re quite sparse on detail, but we love them because they get us into unfamiliar neighborhoods. Unlike the Rick Steves tours, these seem to avoid major sites in favor of places that are somewhat off-the-beaten-path from a tourism standpoint. If we’re staying in a city for a month, we try to complete every tour in the book.

- Airbnb Experiences: Beyond its well-known focus on places to stay, Airbnb also has an offering called Airbnb Experiences, which is marketed as a way to connect with the local culture by taking cooking classes, food tastings, market tours, history tours, and more. The vast majority of Airbnb Experiences we’ve done have been fantastic—sometimes even moving. We learned about jamón ibérico in Madrid with a third-generation owner of a ham store, made bread and tartines with a chef in Napa Valley, got a mind-bogglingly delicious tour of a Parisian market with a charismatic food writer, cooked traditional Moroccan food in a woman’s home in Marrakech, and took a history tour in Croatia with a woman whose family fled during the 1990s war in the Balkans. Withlocals has similar small group tours, but I haven’t tried them yet.

- Get Your Guide and TripAdvisor also offer tours and experiences, but the groups tend to be larger, and the guides are less personally connected to the places they are describing. We’ve only done a few of these.

- So-called “free” walking tours are heavily advertised within cities and are usually decent, although they can feel scripted or dispassionate, and the group sizes tend to be large. Tour guides expect a tip of $10–20 per person, although paying is officially optional.

- Beyond guided tours, wandering aimlessly is a great way to get a feel for a city’s pulse. Sometimes it’s best to toss structure aside and join the long tradition of flâneurs. In addition to exploring the streets, a long wander through a foreign grocery store is one of the world’s great free activities, providing many clues about local culture and tradition. Specialty grocery stores serving immigrant communities (e.g. an Asian grocery store in a European city) are especially interesting.

We look for discounts on museums & sights

Surprisingly, our love of sightseeing has not subsided after many years of being nomadic. We keep our eyes peeled for ways to reduce costs:

- City-wide discount cards: Many cities have some kind of card that you can use to get unlimited access to sights and museums in a city. You usually have to hit the sights really hard to make these passes worth it, but we utilize them if we feel up for an intense whirlwind weekend of sightseeing and museum-going.

- U.S. National Parks Pass: At only $80, an annual pass is an unbelievable value for the money because it includes unlimited admission to any national park in the United States. We’ve visited 15 parks and monuments so far, and they are all fabulous—especially the Mighty 5 in Utah.

- Annual museum pass: When we were traveling in North America, we bought a Carnegie Museums annual pass, which has reciprocal privileges in many museums around the country. Buying a local museum pass for Pittsburgh may seem like a counterintuitive strategy for nomads, but it got us free admission to museums in New York, Denver, Montreal, and more.

- Free days: Many museums have a free day once per month, so it’s worth checking their websites to see what is available. Free days tend to be crowded, but for expensive museums, it can be a worthwhile tradeoff.

- Free museums, events, or sights: Some expensive cities like London have a wealth of free things to do, which makes visiting them a great value for the money. You don’t need to spend a ton of money to have a great time.

Lodging

Airbnbs are great for long stays

We primarily stay in Airbnbs and plan to continue doing so. Thoughts:

- They’re reasonably priced for long stays. Week-long stays tend to come with a 5–20% discount, while month-long stays typically offer a 10–40% discount. Those discounts make a big difference in terms of affordability. The cost of living in Airbnbs full-time is not dramatically different than paying rent in a major US city. It’s possible to get a really nice 1-bedroom apartment in most European cities for $1500–2500 per month. That may seem expensive, but there are many everyday house-related costs that you don’t incur when living in an Airbnb: internet, electricity, water, heat, air conditioning, trash, regular maintenance, property taxes, homeowners association fees, etc. I’m surprised to say that we’re saving more money being nomadic than we saved living in Pittsburgh, despite spending more than normal on our rent.

- A detailed Airbnb checklist is helpful. When we’re staying somewhere for a month, we typically save 10–20 promising Airbnbs, and then we chat about each one as we remove them one-by-one until we’re down to a list of only a few places. Once we’ve found the place that seems like the best option available, given its niceness, cost, and location, we run through a checklist that we created of our must-haves. One of us reads each checklist item out loud, and the other person checks the listing’s text and photos carefully to confirm each item. Download our checklist.

- Good Airbnb ratings are important. We’re cautious with how we communicate with hosts, and we try to leave Airbnbs slightly cleaner than they were when we checked in. Getting even one bad Airbnb guest rating is an existential threat to living this lifestyle, so we do everything we can to be responsible, quiet, easygoing, and clean guests. We are also careful not to annoy our host’s neighbors by stomping around our apartment or being loud in shared hallways or stairwells.

- We try to rent Airbnbs from people rather than companies. An increasing number of Airbnb listings are owned by companies that have essentially cobbled together a hotel out of individual apartments. We try to avoid these places, if only because the apartments tend to be sterile and hotel-like. We prefer to rent from a regular person when possible.

- Airbnb’s impact on cities is a hotly-debated issue, especially because it somewhat increases the average price of rent for local residents due to a reduction in housing supply, especially in historical areas where new buildings cannot be built by law. Increasingly, cities and governments are having a conversation about the impact of short-term rentals and experimenting with local regulation to create better outcomes. For example, Lisbon plans to pay landlords to convert their short-term Airbnb rentals back into long-term rentals, and Amsterdam has banned Airbnbs in the city center outright. The New York Times had a thoughtful article in October 2020 summarizing these tensions. (My sense is that Airbnb somewhat exacerbates a larger structural housing problem, but gets more than its fair share of the blame because it’s an easy scapegoat. In many cities, there are too many forces preventing more housing supply from meeting the demand — outdated single-family zoning, cohabitation bans, nimbyism, amorphous architectural requirements, or regulatory red tape.)

We also stay in a few non-Airbnb places

- Hotels via Booking.com: Airbnbs come with some logistical complexity: communicating with hosts, unpredictable check-in experiences, cleaning fees, service fees, and getting rated at the end of your stay. For a short stay of only a few days, it’s not really worth it. Although we haven’t extensively surveyed the many options available, we’ve had good experiences with Booking.com for quick overnight side trips on the weekend. We don’t overthink these — picking a place to stay rarely takes more than 20 minutes. The only trouble we’ve had with Booking was when we rented a room a few hours before our arrival in Budva, Montenegro, only to discover the hotel we booked had closed for the season. It’s smart to book a few days in advance if you can.

- With friends and family: Like most people, our friends and families like to see us periodically and are happy to have us stay with them for up to a week or so. From a strictly financial standpoint, an interesting aspect of being a nomad is that you’re not paying rent at all when you’re staying at a friend or family member’s house. I used to visit my parents each year for a few weeks around the holidays while still paying rent back in Pittsburgh. Now, an identical visit comes along with hundreds of dollars of cost savings because I’m not leaving a paid apartment behind. Only paying rent for ~10 months out of the year is a big factor in making nomadic life affordable. However, it can be really hard to work from a friend or family member’s house, so be sure to set some expectations or boundaries in advance for how, when, and where you need to work.

- Airbnb and Booking might be prohibitively expensive for solo travelers, younger travelers, or people trying to scrape together a living on the road. I lived in the shared dorm rooms of hostels for 438 days straight in 2006 and 2007, so I totally understand price being the primary factor for people when looking for accommodation. Check out Hostelworld, Hostelbookers, Couchsurfing, or the rapidly-changing landscape of co-living housing aimed at younger or solo nomads. I’m 37-years-old now, so the thought of living with a bunch of other nomads increasingly sounds hellish, but I would have loved it 10 or 15 years ago. Do what feels right to you.

We’ve slowly optimized how and when we move

- We only move on Saturdays: We typically check out of our apartments on Saturday mornings, spend the day in transit, and get settled into a new place on Saturday afternoons or evenings. Airbnb gives monthly discounts for a 28-night stay or longer. Checking in on a Saturday and leaving on a Saturday four weeks later is exactly 28 days. Similarly, Airbnb’s weekly discount kicks in at 7 days or more, so the Saturday-to-Saturday plan works for week-long stays also. Moving on Saturday gives us a chance to get settled, set up our workspaces, test the internet, fix any connectivity issues, or figure out a backup plan before work on Monday.

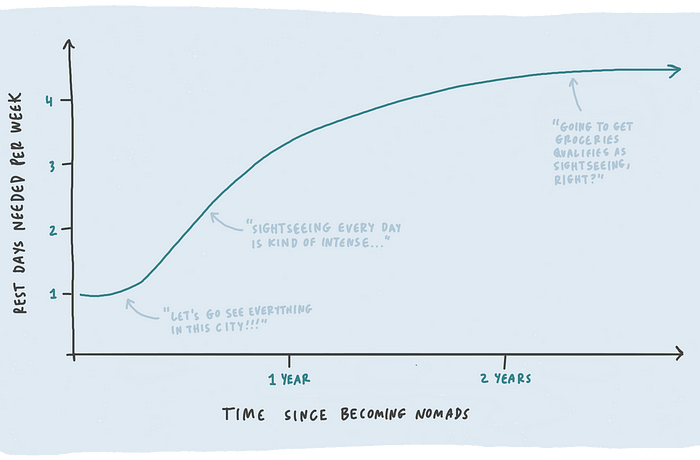

- We stay in cities for at least two weeks: A week is a long time to spend in a city when you’re on vacation, but it’s not nearly enough if you’re a nomad with a full-time job. Early on, we had a few stretches of this journey where we’ve moved to a new city every Saturday, and it was genuinely exhausting. Unless we’re visiting a tiny town, we’ve found that we need to spend two weeks in each location to explore it much at all. In a big city like New York, Paris, or London, a month is our minimum stay. The longer we’ve traveled, the longer our stays have become.

- We have a routine for when we arrive: Before we unpack, we take about a hundred pictures of every corner of the apartment so that we have a detailed record of how it was when we moved in. Then we hang our clothes, put things in drawers, put our toiletries in the bathroom, put our spices in the kitchen, and fully move in. We often move furniture when we arrive, especially desks and lamps to create two workspaces in two separate rooms. Completely unpacking and moving an apartment’s furniture makes an Airbnb feel like home almost immediately. Living out of backpacks can get tiring, so we hide our big backpacks in a closet somewhere until it’s time to move out.

- We have a routine for when we leave: We thoroughly clean the apartment and try to leave it comparable to when we arrived. As we clean, we reference our arrival photos to move furniture back to where it was. Once we’re 100% packed up and have our stuff by the door, we pause and take 10 minutes to look in a few easy-to-forget places: drawers and closets, under the bed and couch, in power outlets, in the bathroom and shower, and in the refrigerator and freezer. Even though we’ve moved more than 100 times in the last 800 days, we’ve only left a few things behind because of this little 10-minute ritual. We almost always find something.

Work

We have plenty of gear to get work done

- Laptop: We both have standard 16" MacBook Pros, which are great for nomads because they nicely balance portability, weight, and screen size.

- iPad: We both use an 11" iPad Pro as a second monitor, which works well with Apple’s recently-introduced Sidecar functionality. We both have small tripods with an iPad mount that allows our iPads to sit just above our MacBook screens, which helps us be less hunched over while we work. I assume the larger 12.9" iPad Pro would be an even better second monitor, but its size is a bit unwieldy for me. Beyond the second monitor, we also use our iPads as tablets, and we each have an Apple Pencil for sketching.

- iPhone: We both have iPhones as our personal phones, but we end up using them often for work.

- Wall adapter: I use an Epicka universal wall adapter, which I like a lot. The end that fits into the wall adapts to common types of outlets globally, including the standard European, US, and UK varieties. The other side lets you plug in electronics from almost anywhere, although I only use it for my three-pronged US-style MacBook Pro cable and my electric razor. The adapter also has 1 USB-C port and 4 USB-A ports, so many other things can charge while I have my computer plugged in.

- Wired headphones: In my opinion, wireless Bluetooth headphones like AirPods die too quickly and often to be useful at work. I rely on the standard-issue wired Apple EarPods instead, which are lightweight, unobtrusive, and have a decent microphone so people can hear you.

- WiFi Hotspot: We bought a WiFi hotspot in Portugal, which allows us to insert a local SIM card as an internet backup plan. (More on this later.)

- Random cables and adapters: It is essential to be confident about our technology and have backup plans if things fail. If we can’t work because we lost our headphones or forgot some random dongle, we threaten our ability to live this way — it’s worth bringing a lot of gear. My electronics organizer is jam-packed and contains a lot of technological fallbacks in case something stops working.

We rely on software to get work done remotely

Although I use specialty software like Figma or Adobe Creative Cloud to do product design work, some of my go-to tools would be useful for any nomad:

- Google Workspace (formerly known as GSuite) for email and calendars, plus some occasional documents, spreadsheets, or slideshows.

- Loom to quickly explain ideas via screen-sharing and video. Loom helps work happen asynchronously and can prevent unnecessary meetings. Zoom has been good for remote work, but I’d argue that Loom is better.

- MURAL is a digital whiteboard to capture thoughts, do work, give presentations, or collaborate visually during meetings. (I like this product so much that I got a job there as a product designer in 2021).

- Notion is a flexible app for storing information. I use it as a personal wiki where I organize notes from 1-on-1 chats, meetings, research, etc.

- Slack to communicate with our coworkers both synchronously and asynchronously. Slack is both magical and totally overwhelming.

- Things is a great personal to-do list app for iPhone, iPad, and Mac.

- Zoom for video chats and meetings. Zoom is sometimes glitchy and unreliable, but it’s the best thing available, unfortunately.

Our workspace needs are relatively simple

We work from our Airbnbs rather than seeking out a different place to work. This blurs the line between “home” and “work” too much for some people, but for us, it works just fine.

- We need a quiet space for phone calls: Our office needs are minimal — we mostly need a quiet place to have video calls over the internet with our far-flung coworkers.

- We need two distinct rooms: We sometimes sit at the same table to work during the day, but we often each have simultaneous meetings that we need to join. We’re careful to choose apartments with a solid wall and door between the bedroom and living space. We try to visually confirm this in photos rather than just relying on a search for “1 bedroom” apartments.

- We need two different desks: We seek out apartments with at least one legitimate desk beyond the kitchen table. This eliminates about 75% of apartments because many Airbnbs have bedrooms without desks.

- Co-working spaces aren’t useful for us: When we started planning this journey in 2017, we imagined that co-working spaces would be ideal places to work. Most co-working spaces are big shared rooms, plus a few cramped and sought-after phone booths for making an occasional phone call. All we need is unrestricted, all-day access to a phone booth with fast internet, which co-working spaces barely provide. Moreover, once we moved to Europe, we discovered that many local co-working spaces are closed by the time our workday ends at 10–11 pm. Still, it’s worth researching a membership with a co-working chain like WeWork All Access or Spaces Coworking in case these are a good fit for your needs.

- Coffee shops aren’t useful either: Like co-working spaces, coffee shops tend to be too loud and they close too early. We have 3-4 hours of video calls per day, which requires a lot of talking loudly at our computer screens — it’s too awkward and disruptive to do in public.

Having decent internet is critical (but sadly unpredictable)

The internet has been reliable enough to have glitch-free video calls in about 75% of the Airbnbs we have called home. Before we had a good backup plan for bad internet, we tried a bunch of problematic options:

- Co-working spaces. In Marrakech, we were lucky to find a co-working space with long opening hours, reservable phone booths, great internet, and a cheap weekly rate. Rare!

- Hotel conference rooms. Our Airbnb’s internet was completely broken in Conwy, Wales. We booked a conference room at a nearby hotel to use for one day (at an unsustainably pricey £50 per day) because we had a high-stakes presentation to give at work. Later in the week, we were nice enough to the hotel’s staff to let us use an empty conference room for free if we bought coffee once in a while.

- Hotel rooms. Hotels sometimes charge upwards of $20 per night for lackluster internet, and when the internet is free, it typically moves at glacial speeds. If it’s broken, nobody on staff seems to know how to fix it. As a result, we never try to work from hotels.

- Buying a local SIM card for a Zoom call’s audio. In Copenhagen, we tried using a local SIM card to join Zoom audio via a Danish dial-in phone number, relying on our dodgy Airbnb internet only for the video feed. This was a decent idea because it’s more important for people to hear you than see you, but it was difficult to find a SIM card with many phone call minutes and this way of connecting is far too cumbersome and fiddly.

These days, we rely on two backup plans in case of sluggish Airbnb internet, both of which work relatively well in a pinch:

- Plan A: Use a local SIM card and a portable hotspot. We bought a wireless hotspot that has a slot to hold a local SIM card. This requires us to get a new SIM card periodically, but it allows us to connect to Zoom meetings from our laptops. A hotspot is still a bit clunky, but it’s a fantastic backup plan if your job depends on reliable connectivity. (There are services like Skyroam that tie global data coverage plans to a hotspot device, but reviews online are a mixed bag, so we didn’t go this route.)

- Plan B: Use the phone’s data for video calls. We put our phones on a tripod and use its Google Fi data plan (more on this later) and camera for video calls, relying on the janky Airbnb internet connection only for web browsing, which doesn’t slurp data as much as a video call. Zoom is not ideal on a phone because the screen is tiny, and screen-sharing is nearly impossible, but it’s better than a bad connection.

Working at night in Europe is a huge life upgrade

We work at the same time as our coworkers back in Pittsburgh and San Francisco. Depending on where we are in Europe, we start our workday at 2:00 or 3:00 pm and end the day around 11:00 pm or midnight.

- Advantages: Having free time on weekday mornings is fantastic because markets, museums, restaurants, and sights tend to be open. Mornings spent exploring in the daylight is single-handedly my favorite thing about our lifestyle. It has hugely improved my mental health, especially in the short and dreary days of winter. Why waste the daylight staring at a computer screen, only to have your free time in the dark?

- Disadvantages: Doing anything fun at night has been difficult. Still, we do shift around our work schedules on occasion (or use some vacation time) to go out to dinner, attend a concert, or see a play.

More thoughts on working remotely as a nomad

- The coronavirus pandemic caused a lot of office workers to become suddenly remote. My hunch is that most companies will be explicitly remote-friendly or remote-first in the future, but it’s hard to say with certainty. (Even pre-pandemic, most office-based companies were semi-remote, even if they were in denial about it. On any given day, a non-trivial percentage of the employees working away from the headquarters — at home, satellite offices, separate buildings, airports, hotel rooms, etc.)

- If your company has an in-person office, schedule regular unstructured chats with trusted friends at the office. When our nomadic journey began, we felt less connected to the serendipitous hallway conversations at work. We had less of a sense of the company’s momentum and the feel at the office. Are people chipper? Disgruntled? Are things improving? Getting more challenging? It’s hard to tell these things remotely when there’s a lot of little stuff happening in the office that isn’t relayed on Slack or in meetings. Having a few friends at the office is essential because working for a semi-remote company can feel isolating.

- Better still, work for a remote-friendly company: I’m convinced that remote work can be just as effective as in-person work, but only if people in a company embrace it fully. New digital nomads should strongly consider working for an explicitly remote-friendly company rather than one based primarily in an office. It’s not fun being a second-class citizen that people begrudgingly have to keep in the loop — if everyone is remote already, being a nomad is just a step beyond the status quo, rather than a bizarre and unprecedented exception.

Travel and transit

We rely on many modes of transportation

- Walking: Unless we’re in a hurry, we walk almost everywhere we go. Exploring an unfamiliar city on-foot brings us endless amounts of joy.

- Local bus, tram, or subway: If something isn’t walkable, this is our main way to get across a city. When we stay in a new city for a month, we often invest in a transit pass for the entire month. Although pricey at around $80–100 per month, having a pass gives us an incentive to explore more than we otherwise would. If we’re staying away from the city center, we’re especially likely to buy one. We used our passes enough in New York, London, and Paris to be well worth the big up-front cost.

- Trains: Trains in Europe are getting faster and faster, but even when they’re slow, they’re still our preferred way to travel. For me, an 8-hour train ride is much less stressful than a 6-hour bus ride or 2-hour flight. Trains typically cost about 30% more than buses, however.

- City bike shares: Our favorite bike share programs are dockless, where you can ride from Point A to Point B and leave your bike anywhere within a large perimeter zone. The best service we’ve encountered so far is Donkey Republic in Copenhagen (and many other cities in Europe), which is a good value at €20/month for unlimited rides under an hour in length. The bikes are plentiful, rentable with an app, and have a phone holder on the handlebars so we can load up biking directions to follow during the ride. Bike-sharing systems with docks tend to be harder to use due to their clunky kiosks and fixed points where bikes can be returned, which requires some planning before every ride. Even though it makes us look dorky and profoundly non-European, we brought helmets with us and wear them religiously when biking. Better dorky than dead.

- Bike rental: Cities without bike-sharing systems almost always have good and inexpensive rental shops where a bike can be rented for $10–20 per day. If we plan to bike all day, we check with the rental shop about closing times or options for returning it the next day just in case.

- Scooters: People like to gripe about the scooters popping up in cities worldwide, but I don’t think the complaints are completely justified. Scooters are much quieter, cleaner, and less disruptive than cars — plus they’re fun to ride, pair nicely with other modes of transit, and occasionally are the best transit option available. They were the same price but twice as fast as buses in Salt Lake City, and we regularly relied on them to get from our house to the BART in Oakland.

- Lyft and Uber: We often used Lyft and Uber to get around living in the US, but we don’t use these services much anymore. Our tolerance for walking long distances is much higher than it used to be — the walks never become boring because we’re always in new places, we rarely commute because we work from home, and cars are much less necessary outside of the US.

- Renting a car: Driving is a great way to see the countryside, get off the tourist trail, and be in full control of the timing of your day. For every other reason, driving is terrible. Renting a car is cumbersome and expensive, navigating quirky roads and wackadoo roundabouts in unfamiliar countries can be legitimately scary, and parking is a hassle. It’s also easy to get speeding tickets or other unexpected fines, like the €300 fine we got entering Slovenia without a special vignette sticker on our windshield. Thankfully, my girlfriend Ali inexplicably likes to drive, and I can just curmudgeonly serve as our navigator.

- Camper van: We rented a camper van twice while in Portugal and loved it. If you have a week of vacation from work, renting a van in one city and returning it a week later in another is a great way to move. We never worked from the van because it seemed like it would be too unpredictable.

- Flying: We’ve flown about twenty times since we became Nomadic in 2018, including trips to and from Europe twice, and at least 14 of our flights have been effectively free, paid for with points we’ve earned just by using our credit card. Although we typically travel overland, we have almost always racked up enough credit card points to pay for our next flight. (More on that in the “useful products & services” section below.) When you fly internationally, always check-in at a desk staffed by a person — you almost always need to have an airline employee review your passport and stamp your boarding pass before flying, even when it doesn’t seem like you do.

We use Google Maps constantly

Transit directions on Google Maps are one of the most essential tools for getting around. We’ve used walking, biking, and driving directions, but we especially rely on public transit directions. In every city we’ve visited, Google Maps has had straightforward transit directions that succinctly describe all of the details: what modes of transit are available, which lines to take, and what direction to go. It still feels like magic to confidently ride any public transportation system in the world. A few tips:

- We set our temporary address as Home in Google Maps every time we move, so we don’t need to remember our constantly changing addresses when we need transit directions.

- Google’s walking directions are unrealistically fast. If the directions say it will take 45 minutes to walk somewhere, know that it will take 45 minutes going at a speedy pace without ever stopping. Always allow extra time.

- If you zoom-in on bus directions, Google Maps typically shows the exact location of the bus stop, including what side of the street it’s on.

For longer journeys, we research transit options in advance

We use Google Maps for 80-90% of local train or bus information, but we find ourselves using a few other websites, especially for international journeys.

- Rome2rio is a website that displays different options for getting from one city to another, which is handy if you’re trying to get a feel for what options are available (e.g., train, bus, car, etc.) and their relative costs.

- Omio is similar, although it is more oriented toward purchasing tickets. Each ticket is a bit more expensive than purchasing directly through a transit agency, but sometimes it is worth the convenience.

- The Man in Seat 61 offers astoundingly detailed descriptions of most European train journeys. Run by Englishman Mark Smith, the site has been around since the early days of the Internet. When we took an overnight train from Berlin to Budapest, Seat 61 was a great place to get a feel for what to expect. I have a soft spot in my heart for this website — it’s fun to explore even if you have no upcoming travel plans at all.

- Die Bahn is Germany’s national railway service, which seems to have its finger-on-the-pulse of the latest train information throughout Europe. I’ve found the timetables to be more complete and accurate than any other source, and ticket prices are slightly lower than Omio. (Although, Die Bahn is a much clunkier website, and certain screens will jettison the English language in favor of the website’s mother tongue. Scheiße!)

Useful products and services

None of these recommendations are paid sponsorships in disguise, although some do contain Amazon referral links. I also don’t necessarily recommend these strongly, but they’re all good enough to mention.

We carry Osprey travel backpacks

Ali has an Osprey Fairview 55, and I have an Osprey Farpoint 55 backpack, both designed for long-term travel. I haven’t looked extensively at suitcases or backpacks for nomads, but I like my Osprey pack so much that I haven’t ever wanted to look for alternatives. What I like:

- They have a fantastic daypack: We use the sturdy daypack far more than the rest of the pack because we’re not carrying all of our stuff that often since we only move about once per month. The daypack includes a padded laptop sleeve where a 16" MacBook Pro fits perfectly.

- They (kind of) qualify as carry-ons: When you zip off the detachable daypack and use it as a personal item, the pack is just barely small enough to qualify as a carry-on on most airlines. If our bags are jam-packed, airline employees seem to give our bags extra scrutiny, however, and we’ve been asked to gate-check our big packs a few times.

- Checking the pack is great too: When checking the backpack onto an airplane, all of the backpack’s straps and exterior accouterments stow behind a zippered pouch, making it less likely to get snagged on a conveyor belt in transit.

- They’re not top-loading: The pack fully opens with a giant zipper, making it more like a regular suitcase than a top-loading hiking backpack.

We use a few other things to carry our stuff

- Compression stuff sacks allow us to cram more clothes into our backpacks. Our clothes get somewhat wrinkled in transit, but it’s nothing a few days on hangers can’t fix. I have two sizes of compression sacks from Alps Mountaineering (10 and 20 liters) and their durability is impressive. Ali got one from Sea to Summit, and it has started to fall apart. I keep a sturdy laundry bag inside the same compression sack when we’re in transit, so as my clothes get dirty, I can continue to put them in the same place as the clean clothes, but keep them separated for smelliness reasons.

- Packing cubes and pouches: Eagle Creek makes nice packing cubes and pouches that help organize random stuff inside our packs. I recommend getting these in distinct shapes or colors so that you can tell each one apart inside of your pack.

- Reusable shopping bags. Plastic shopping bags are rare in Europe, bad for the environment, and cost extra money at the checkout. We’ve invested in two high-quality shopping bags made by Loqi that we bring with us almost everywhere. We bought them on a whim at a museum shop, and I’ve been impressed by their sturdiness and ability to carry weight.

- Large tote bag: After two nomadic years, we got a sturdy tote bag from LL Bean, which we use for moving and grocery shopping. It carries a hell of a lot of weight, zips closed on the top, and is a good carry-on when we check our big backpacks on an airplane. Something along these lines is a useful second bag in addition to a big backpack.

- Recycling bags: Airbnbs almost never have places to sort recycling before it goes out, so we bring our own. We have two bags like this to hold and separate our recycling at home. Recycling rules differ from place to place, but one of them typically holds glass and the other plastic and metal. A third paper grocery bag holds our paper recycling.

We bring some cooking supplies with us

Airbnbs usually have equipment for cooking that is just barely good enough, so we carry some gear with us from place to place:

- Chef’s knife: There’s some kind of global consensus that decent knives have no place in rental apartments like Airbnb — they’re almost universally small, dull, or both. Cooking is much more fun with a good knife, so we bring a chef’s knife with us. We don’t fly very often, but when we do, we check a bag so that the knife doesn’t get confiscated.

- Prep bowls: We use silicone baking cups for preparing ingredients before cooking or serving snacks or dips.

- Herbs & spices: We have slowly built up a pretty comprehensive spice kit. We’ve bought containers for our spices and cooking liquids at the delightful Flying Tiger stores scattered all over Europe, and we occasionally top-up our collection with spices we find in an Airbnb.

- Peeler: Airbnbs often have a bad peeler or no peeler at all, so we bring the classic OXO Good Grips peeler with us.

- Olive oil, vinegar, hot sauce, etc. It’s hard to perfectly time usage of this stuff when you’re moving all the time, so we just bring it with us.

- Potholders: Even when an Airbnb has an oven, they often inexplicably don’t have pot holders or trivets, so we bring a few with us to avoid having to dangerously improvise when we pull food out of the oven.

- Bag for random condiments: We keep leftover packets of sugar, ketchup, or mustard so that we don’t have to buy those ingredients.

- Insulated lunch box with ice packs: We have a lunchbox similar to this one, which is useful when we’re going to a market or a grocery store and not heading home right away, when we’re moving, or when we’re out on a day trip and want to pack a lunch. It has small ice packs, which we keep in the freezer until the lunchbox is needed.

- Small cutting board: Useful in the lunch box during a picnic, or when we both want to prep for dinner simultaneously in an apartment with only one cutting board.

- Small box grater: Graters are only in about half of Airbnbs, so we picked up a small grater like this one to compensate.

- Measuring spoons: Airbnbs seldom have these, and cooking is certainly easier with them. The ones we bought from Flying Tiger are just okay, but these collapsable measuring spoons and cups look ideal.

- Reusable containers: We use beeswax wraps instead of buying plastic wrap, reusable silicone bags instead of buying Ziploc bags, and reusable produce bags instead of using the plastic ones at grocery stores. Beyond any environmental benefits, these are useful when we have leftover food because we can’t take an apartment’s containers with us when we move.

- Collapsable coffee filter: Most Airbnbs have some kind of way to make coffee, but sometimes there’s no coffee maker at all, or it’s the kind with the wasteful plastic pods. We bring our own ground coffee and use the X-Brew by Sea to Summit if there’s no better option available in an apartment. This lets us make coffee in a device that folds relatively flat. It works better with paper filters, so we carry those too. We brew the coffee into a Hydroflask water bottle, which stays hot for several hours.

- Rubber bands and twist ties: These are as useful as a nomad as they are as a non-nomad, so we hoard these and bring them in our kitchen kit.

We’re prepared for most weather conditions

Although we avoid extreme temperatures as much as we can, we’re always ready for inclement weather.

- Cold and rain: I have a knit stocking cap, medium-weight winter gloves, a pair of long thermal underwear, a light puffy jacket, and a high-quality rain jacket. Having two light jackets — one waterproof and one not — is great as a nomad because they make a decent winter coat when layered, but they’re both useful on their own year-round. It’s worth investing in a good travel umbrella, not some dinky little travel umbrella that’s going to fall apart in a bad storm. We also each carry pack covers in case we need to move when it’s raining.

- Heat: We don’t do anything particularly novel or clever here — just lots of t-shirts, a few pairs of shorts, a hat, a swimsuit, a tiny travel towel for beaches, a bandana, and plenty of sunscreen.

- Night: Because we like to go on long exploratory hikes and bike rides, we always bring a small kit of gear with us if it gets dark while we’re out on a trail or rural road somewhere. We have a headlamp, two white and two red safety lights, and two reflective leg bands. This may seem overcautious, but we’ve found that it’s liberating to not have to worry about being home before it gets dark.

- I primarily use the great app WeatherLine to see upcoming weather. If we’re spending a lot of time outside (e.g., on a multi-day bike trip) I check the Apple Weather and The Weather Channel apps to see potentially conflicting forecasts, which happens surprisingly often.

We’re prepared for many health situations

- Insurance: Our healthcare is cobbled together from a few different sources: our normal US-based health insurance through our jobs, some overseas emergency coverage we get through our credit card, and extra European-specific coverage we got through IMG Global. We’ve never used our European insurance, so I can’t vouch for it apart from it being fairly easy to buy and renew as we travel. Nomad-oriented coverage is also available via World Nomads, SafetyWing, and others, so it’s worth shopping around and reading lots of reviews.

- A comprehensive first-aid kit: We have a typical first-aid kit supplemented with a few upgrades: Dramamine for motion-sickness, liquid bandages in case we cut ourselves while cooking, moleskin patches for blisters, prescription antibiotics for travel diarrhea, and an abundant supply of our regular prescriptions.

- European pharmacies: We’re going to the doctor and dentist less than normal because our coverage doesn’t pay for typical physicals and check-ups while in Europe. However, European pharmacies are unbelievably handy when you’re sick — consulting with a pharmacist is much more like going to the doctor than it is in the United States.

- Out-of-pocket doctor visits: We have also both gone to doctors in-person in Europe, and the cost is typically between 75 and 100 Euros. We’ve found that doctors can just tell you the final price of a visit up-front, unlike in the US where prices are a mystery until you get a dizzying bill in the mail many weeks later. Most doctors speak English, but many cities have an explicitly English-speaking international clinic aimed at foreigners.

- A tiny pill case: Our schedules are a bit unpredictable, so it’s nice to have a small pill case in our daypack with a few prescription medications, plus some ibuprofen or allergy pills. Especially on days when we’re moving, it’s nice to have a tiny medicine cabinet handy because our normal pills are buried somewhere deep in our large packs.

- Hand sanitizer and wipes: In our nomadic life before the pandemic, I got sick often because we were out in public in new cities and countries all the time. Hand-sanitizer and thorough hand-washing helped me not get sick at all during the pandemic, so I think nomads would be well-advised to continue their pandemic-era hand-washing habits. You’re exposed to a lot of weird germs when you’re constantly on the move.

Chase Sapphire Reserve is an unbelievable credit card for nomads

I have no financial incentive to recommend this credit card, but holy shit — this credit card is amazing. It’s about $500 per year, so I encourage you to research the specifics and see if it makes sense for you. We love it because:

- They give you a $300 travel credit per year for spending a certain dollar amount on travel, which we hit almost immediately every year. Practically speaking, this means that the credit card actually costs $200 per year.

- You get 50,000 points for signing up, which is enough for at least one significant flight (e.g., to Europe or maybe Asia if you’re lucky).

- We earn 3x points on restaurants and travel purchases. Living as a nomad, most of our purchases qualify for 3x points, including our monthly rent. As a result, we rack up points far more quickly than a typical person.

- Chase reimburses you if you buy TSA Precheck, so when we fly in the United States, we get the minor convenience of going through security with slightly shorter lines and less stress because we can leave our shoes on and leave our electronics in our bags.

- There are no international transaction fees, meaning that you can freely use your card in any country without tiny fees on every purchase. This is a must-have if you’re nomadic.

- The card comes with Priority Pass, a network of airport lounges. So far, there has been a lounge in almost every airport we’ve visited, and we’ve enjoyed hundreds of dollars worth of food and drinks in them for free. Once you’re a lounge person, you can never go back. It’s glorious.

- Our points can be transferred 1-to-1 to other airlines. An example of why this is useful: We were trying to fly from Europe back to the US to see our families for the holidays in 2019, and we found flights on the Chase website for about 90,000 Chase points. We found the exact same flight on United’s website for 60,000 United points. We transferred our points out of Chase and into United without losing any points along the way, then bought the flights for a 33% discount.

There are a handful of other perks, but those are the standouts for us. There is an intense and off-putting subculture of “travel hackers” obsessed with optimally using their credit card and airline points. I’ve found most of the advice about this to be puzzling and overly complicated, but I like Dan Frommer’s Points Party because he’s a clear and compelling writer. The main piece of advice on all the websites we looked at was to get the Chase Sapphire Reserve card and aggressively utilize its perks, so we do.

We use a few other financial services

- Apple Pay: Paying for things with a US-based credit card causes confusion internationally because the US is a rare country that forces people to sign receipts, so European cashiers are often baffled when their computer systems tell them that a signature is required. After watching confused cashiers scramble to find a pen many times, we realized that it’s much faster and easier to pay with FaceID and Apple Pay on our phones, which doesn’t require a receipt or signature. (The US has consistently been 3-5 years behind global payment norms, so paying for things in a foreign country often makes me feel like a Luddite hillbilly.)

- Charles Schwab Investor High-Yield Checking has no international transaction fees and waives ATM fees. The website is a little clunky, but otherwise, I like it. We avoid using cash as much as we can because of the aforementioned credit card points, but cash is still necessary periodically. We only use ATMs from legitimate banks, rather than random ones at a restaurant or the dodgy EuroNet ones that are ubiquitous in touristy areas. Even if transaction fees are waived by your bank, you can still get a bad exchange rate. If possible, use an ATM at a big international bank.

- Venmo or Cash App for getting money back and forth to friends or family as needed.

We use Google Fi as our phone service

We did some research about phone plans before we left, and it was a confusing and jumbled mess. T-Mobile offers decent coverage for people visiting Europe for a few days or weeks at a time, but it’s not great as a primary phone provider because international data gets throttled for anything beyond light usage. We settled on Google Fi, which we like because:

- It works from country to country: Google Fi latches on to local phone providers worldwide so we can use our phone in more than 200 countries. Inside the US, it uses both T-Mobile and Sprint depending on which signal is stronger. Outside the US, it does the same thing with local phone providers. Practically speaking, it feels like we have a normal US data plan except that it seamlessly works from country to country. We don’t have to do anything when we cross a border — our phones just switch to a different cellular provider and we rarely even notice.

- It has reasonably plentiful data: Google upgraded our plan to have “unlimited” data, which is a misnomer because they throttle data after 22GB per month, but it’s enough data to use our phones for occasional video calls if we have bad WiFi at an Airbnb.

- It’s possible to make phone calls: We can call US-based numbers for free, even when abroad. If we make local phone calls while we’re traveling (e.g., calling a Portuguese takeout restaurant while we’re in Portugal), those are considered international calls. They’re pricey at 20 cents per minute, but I very rarely use the phone so it’s not a big deal.

Google Fi demands that we’re in the United States for significant chunks of the year, but so far, they have not turned off our service for being outside of the US for long periods of time. If they ever cut us off, we’ll have to park our US numbers somewhere and get local SIM cards instead.

We use Google Translate for translations in a pinch

People worry too much about the language barrier when they travel. Just being friendly, kind, and humble is arguably more important than learning a foreign language for travelers. You’ll be fine if you learn the words for hello, goodbye, thank you, sorry, yes, no, and cheers. Anything else will help you connect with a place more deeply, but it’s not absolutely essential.

Still, there are some unexpected situations when fully traversing the language barrier is necessary, which is when we use Google Translate. An underrated feature of the app is that you can turn your phone sideways to see a larger version of the translated message. It’s incredibly helpful to be able to type a message, twist your phone, hand it across the desk at a pharmacy or train station, and have the person on the other side understand your intent.

More useful digital services

- Amazon Locker: I accidentally left my flip-flops on the shores of Lake Powell in Utah. A few days later, I picked up their exact replacement at an Amazon Locker inside of a 7–11 in Denver. Amazon Locker is handy when you don’t have a home address because you can get particular things delivered to wherever you happen to be. We’ve seen Amazon Lockers in Europe, but it doesn’t seem like a US-based Amazon account can deliver things to them, but maybe that restriction will eventually change.

- Apple Photos with iCloud Photo Library is a fairly painless way to ensure your photos are constantly backing up as you travel.

- AppleTV+ is a streaming service that works anywhere because Apple creates all of the content and they don’t have country-by-country licensing issues. The selection is a bit sparse, however.

- Disney+ works anywhere for the same reasons, and it includes a surprising amount of content.

- Dropbox is a useful place to put all of your digital files while on the road. As a nomad, I have boosted my reliance on cloud-based storage in case my devices are lost or stolen.

- Hulu only works if you use a VPN (see below) to simulate a US-based internet connection.

- FaceTime is a good video chat tool if your friends and family have Apple devices. Ali sometimes puts her phone on a tripod and hangs out with her sister back in Minnesota for long periods of time — cooking together, chatting with her kids, etc. These kinds of low-pressure and low-key video chats are helpful to feel more connected as a nomad. FaceTime also works remarkably well on 4G LTE connections, which allows Ali to chat with her young niece and nephews while we’re out and about without having to plan every video chat. You can do group chats on FaceTime too.

- The Fork is good for making restaurant reservations in unfamiliar cities.

- Figure It Out is a browser extension for Chrome that allows you to see what time it is in many time zones simultaneously, which is useful if you have coworkers spread across the globe.

- Layered City is an iPhone app that I designed, wrote, and programmed during the coronavirus pandemic. It collects the internet’s best content (podcast episodes, videos, and audio tours) about cities in Europe.

- Libby is a service that allows you to check out ebooks or audiobooks from your local library. You need a library card number to get an account, but otherwise, it’s akin to using Kindle or Apple Books.

- Marco Polo is like FaceTime but asynchronous, where you essentially leave each other video messages. It’s a great group chat tool and is especially handy when talking to people in other time zones because you don’t need to chat with each other simultaneously. It’s a good way to make keeping in touch feel more loose and informal.

- Netflix works wherever we are, although the selection varies dramatically from country to country unless you use a VPN to access a specific country’s Netflix selection.

- NomadList is used by many nomads, but I’ve never found it to be very useful. The irreverent neighborhood maps of each city are fun, though.

- Overcast is an excellent podcast player for iPhone or iPad that I use daily. I seek out podcasts or podcast episodes about the place we’re visiting. This has helped me find gems like The Europeans or The Land of Desire.

- Picture This is a great iPhone app that allows you to take a picture of a plant and learn what it’s called. Considering I’m not a plant nerd at all, I use this surprisingly often.

- Pluto is a well-designed travel planning app. We have our own complicated system for travel planning (described above), but this is similar to our home-grown version.

- Reddit has a thriving Digital Nomad subreddit. I don’t really use Reddit, but I’ve heard good things about this community.

- Slack is known for its use at work, but there are many just-for-fun communities that you can join based on hobbies or industries too. You have to seek these out or get an invitation, however.

- Spotify’s music streaming service works worldwide, seemingly without difference from country to country as we move. Playlists are a good way to discover local music, whether it’s classic styles like Spanish Flamenco and Portuguese Fado, or something more modern.

- UberEats is widely available for food delivery. Most cities have a few competing services (like Glovo in Portugal), but sometimes you need a local phone number to actually sign up for them, so we tend to use UberEats or just order takeaway directly with a restaurant, which saves the restaurant money.

- Voice Memos: Apple’s built-in voice memos app is useful as a supplement to taking photos or video. I love being able to discreetly capture interesting or unusual sounds around me. If I can, I change the titles of the voice memos right away so that I don’t end up with hundreds of unlabeled audio recordings.

- VPN / Virtual Private Network: Many TV shows and movies available on streaming services like Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Hulu are restricted to be viewed in different countries. I use Express VPN, which tricks a streaming service into thinking we’re watching from a specific country. It works reasonably well, although it’s a bit flaky and sometimes the streaming services (especially Amazon Prime) block us from watching something specifically because we’re using a VPN.

- WhatsApp: Although it’s not hugely popular in the United States, people in Europe all assume that you have WhatsApp and expect to be able to contact you through it.

More useful physical items

- AirPods: I don’t like wireless earbuds for work because their batteries die too quickly, but they’re fantastic in every other context. Original AirPods are nice, or AirPods Pro offer active noise-canceling, which lessens the noisy hum of planes, trains, or subway cars.

- Battery pack: We often spend an entire day away from the house, taking pictures and using maps, two things that are pretty taxing on a phone’s battery. We’ve used an Anker power bank throughout our journey, which we like because it’s relatively small and can charge our phones 3-4 times before its battery dies. Battery packs are a rare technological device that allows you to think less about technology because you’re not fretting about having a charged phone or finding an outlet.

- Carabiners: A few simple carabiners are nice to have around. I often clip our daypack to a chair while we’re eating at an outdoor restaurant to prevent it from getting stolen, or we clip things to our big backpacks while in transit.

- Clothesline: This bungee clothesline is handy when camping, or to supplement a drying rack at an Airbnb.

- Foldable hangers: Airbnbs often have a paltry supply of clothes hangers, so after our first year of being nomads we got 12 foldable travel hangers, and we’re very glad we did. We use them in almost every Airbnb.

- HDMI adapter and cable: If we want to watch a streaming service on an Airbnb TV, we hook up our iPads or laptops using a short HDMI Cable and USB-C to HDMI adapter. After accidentally leaving the cable and adapter in several Airbnbs, we always make sure to leave them in plain sight rather than tucking them behind a TV.

- Money belt: I bring my passport, cash, and a backup credit card in a money belt when we travel from one city to another. Many years ago, I got robbed by a guy with a knife in Cuba, and I was able to calmly give the man my wallet and daypack. Having my passport and most of my money tucked down my pants made it so that my journey could continue, despite the setback. Traveling is typically pretty safe, but a money belt can save the day in case you have an unfortunate run-in with a pickpocket or thief.

- Pocket knife: Having a pocket knife (e.g. a Swiss Army Knife) or multitool (e.g. a Leatherman) is helpful as a tiny toolbox while on the road.

- Sink plug: A universal sink plug isn’t needed 95% of the time, but it’s occasionally a must-have.

- Versatile shoes: I wear a pair of black Onitsuka Tiger 81s, which are great for nomadic life because they’re incredibly versatile. I’ve worn these same shoes every day for almost 10 years, from fine-dining restaurants to hiking the Inca Trail. They’re not ideal in every situation, but they’re always good enough. Versatile shoes like this are a must-have.

Reflections on being a nomad

Positive lifestyle changes

- We’re living more life in less time. It feels like we crammed ten years of life into the last three years. Before being a nomad, there were occasionally years that fluttered by, where it is hard to remember exactly what I did that entire year. As a nomad, almost every day has felt memorable and special, apart from the many repetitive days cloistered indoors during the pandemic.

- We’re having more fun. Being a nomad is fun as hell. We still love living in new cities, settling into new apartments, experiencing new things, eating new food, learning about local history, and meeting new people. Especially on weekends, it feels like being on a never-ending vacation.